Articles

Seasons

Jan 1, 2015

Japanese New Year Culture

With its festive, celebratory atmosphere, and lots of great food to be had, the start of the year is one of the best times to pay Japan a visit.

Of all the numerous holidays and festivals in Japan that take place through the year, perhaps the most significant of all is New Year (known as Shogatsu or Oshogatsu). During this period, businesses are closed from the end of December to the beginning of January, and people from all over Japan would return to their hometowns to spend time with family and friends.

Food, Glorious Food

Unsurprisingly, many Japanese New Year traditions centre around communal eating. Around 11pm on New Year’s Eve, members of the family will gather around to have a bowl of Toshikoshi-soba to symbolise longevity and the crossing over of one year to the next. These noodles are usually eaten with kamaboko (boiled fish cake), spinach, aburaage (fried beancurd) and tenkasu (tempura bits). All the Toshikoshi-soba that’s been prepared has to be finished as it’s considered bad luck to leave any of it behind. This simple dish is usually enjoyed while watching a national television show that features some of Japan’s best-loved singers and performing artistes.

A few days before New Year’s Day, families would also gather together to prepare Osechi, a traditional meal kept in boxes. Osechi is prepared in advance for a couple of reasons: The first is so that the women can enjoy a few days of respite from their usual duties, and also because some people consider it unlucky to work on the first few days of the new year.

The dishes in the Osechi are imbued with significance, too. Daidai, or Japanese bitter orange symbolise good wishes for children in the coming year, while Datemaki (sweet rolled omelette) mark auspiciousness for all. Kamaboko (boiled fish cake) is usually arranged in alternating red and white patterns to signify Japan as the land of the rising sun, while Konbu (seaweed) and Kuro-mame (black soy beans) connote joy and health respectively. Ebi (prawns) are usually skewered and cooked with sake and soy sauce to symbolise longevity, while Nishiki tamago (egg roulade) symbolises wealth and good fortune.

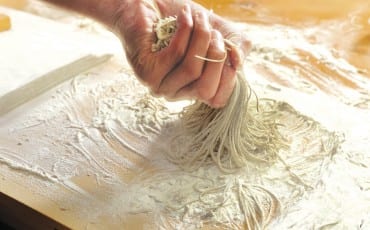

Mochi (rice cakes) are also an integral part of the Japanese New Year. In particular, a special variety known as Kagami mochi is prepared for this time of the year. It consists of two cakes – with the smaller placed atop of the larger – with a Daidai and a leaf placed on top. These two discs of Mochi can mean many things: The human heart; the balance of “yin” and “yang; or the moon and the sun. Kagami means “mirror”, and in Shinto, this represents God. This Mochi is usually left at the home’s Shinto shrine, and is broken and eaten in a Shinto ritual known as Kagami biraki (mirror opening) mostly on the 11th or 15th of January.

Ozoni – a soup containing Mochi – is considered the most auspicious of all dishes that’s consumed at this time of the year. This dish was an important aspect of samurai food culture from around the 14th century, but it eventually became a staple dish of the common people. The preparation of ozoni differs greatly from region to region. In the Kanto region (East), for instance, the soup is flavoured using a stock made with dried bonito or Kombu, while in Kansai (West), the soup is usually made using a white miso.

We highly recommend paying Japan a visit during this time of the year. Not only will you be able to partake in some amazing dining rituals, there are also many games to be played and festivities to be enjoyed, making for a truly memorable trip!

TEXT: DENISE LI