Articles

Seasons

Jan 9, 2020

Let’s CELEBRATE!

The Japanese New Year comes with its own unique customs. Here’s a quick introduction to some of them.

If you’re visiting Japan this time of year, especially in the countryside, you’re in for a treat. Filled with celebratory traditions and customs, the Japanese New Year is a wonderful season. This period is known as Oshogatsu and is perhaps the most important holiday for the Japanese.

New Year’s Eve: Omisoka

As the calendar winds down after Christmas, many people return to their hometowns and the big cities, especially Tokyo, will empty out. It’s the time to prepare for the end of the year with a series of customs and rituals.

To start the year on a clean slate, families begin to spring-clean their homes (like the Chinese for Lunar New Year) from 13 December. This is osoji, or big cleaning, when the entire house is dusted, wiped down and scrubbed while clutter is removed in a flurry of Marie Kondo-inspired activity.

As the year’s end approaches, you’ll notice several types of customary decorations in homes and offices. Made from twisted straw and paper, shime kazari or New Year’s wreath hangs on front doors. Another is the two-tiered kagami mochi, built from rice cakes that are shaped like round mirrors and topped with a bitter orange fruit (daidai). This ancient practice is believed to bring happiness and good luck for the months ahead.

On New Year’s Eve, the Japanese gather to eat soba (toshikoshi soba). Believed to have started during the Edo era (1603 to 1868), the tradition symbolises long life and health as people wolf down the extra-long buckwheat noodles.

New Year’s Day: Ganjitsu

New Year’s Day arrives, and what a big day it is for the Japanese. Ganjitsu refers to the 24 hours of New Year’s Day, and many people will use this opportunity to eat customary food with loved ones, visit a temple or shrine, and yes, shop!

On New Year’s morning (gantan), people will sit down with their families and have a special breakfast known as osechi ryori. Served in a large, elegant bento box (jubako) set in the middle of the table are various traditional food items, each representing a different meaning or wish for the New Year. Shrimps symbolise longevity and fish cakes (kamaboko) are lucky, for instance.

Besides the eating, there is also some drinking with otoso, or New Year’s sake. Sharing the same three cups, families will drink the sake in order of age, starting from the youngest person and ending with the oldest. The idea is to let the older members absorb the energy and vitality from the young people.

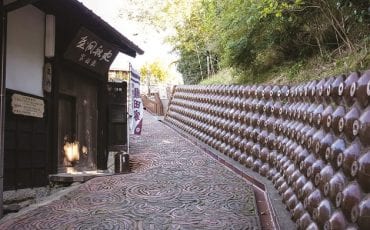

Then it’s off to a shrine or temple in the New Year’s ritual, hatsumode, during the first few days of January, as loved ones pray together for prosperity, health and happiness. Some of the most popular shrines and temples even organise festivities, including rows of stalls selling food and New Year luck charms.

Something a little more worldly but no less traditional is a trip to the shops for the New Year’s special sales — and for the season’s lucky bags known as fukubukuro. Stores fill shopping bags with leftover products from the past year and sell these at a hefty discount in a custom based on a Japanese proverb: “Nokorimono ni wa fuku ga aru. (There is fortune in leftovers.)”

By 4 January, the celebrations wrap up and people begin to return to their day-to-day lives, their minds and bodies refreshed and ready for a new year ahead.